Martin Amis died this weekend and the literary world lost an icon. I have tried to read his work, namely Money. Fortuitously, I was at my parents’ when I heard the news and dug out said book and can confirm I only got to p156, I just couldn’t get into it. I’ve read Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis, Martin’s father, that must count for something? (I highly recommend Lucky Jim, was even talking about it with a pal only a few weeks ago). I am not alone in finding his, Martin’s, work hard to enjoy; it seems he somewhat Marmite.

The reason I originally delved into Martin Amis, and specifically Money, was because I read Hitch-22 by the equally iconic Christopher Hitchens. My friend and I shared his memoir while travelling in Cuba and became acutely obsessed with this man and the time when authors were celebrities. A time when the world was intoxicated by voices and discussion and art and thought. Now, most authors are unrecognisable to the ordinary reader and without some sort of intervention (going viral, celebrity endorsement, an active twitter account or indeed being a celebrity already) remain so.

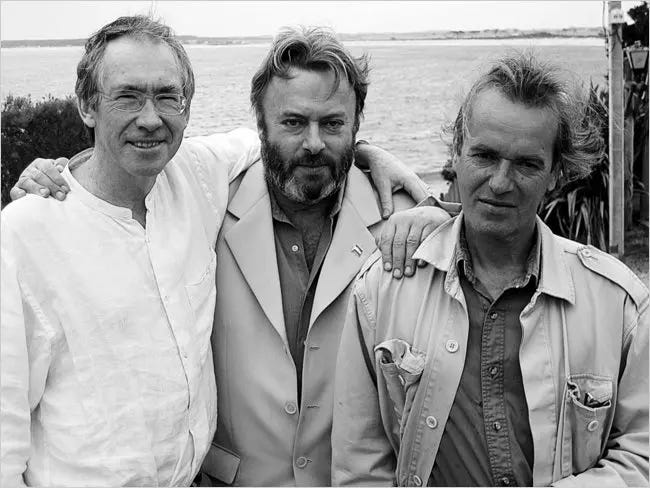

Despite not having read Amis (fair to say 156 pages do not count), he is ever present for anyone with an interest in books. Since I can’t give you a list of the books he has written that I have loved, I am going to segue into another author who was part of the ‘boy’s club’ that ruled the literary hey day of the ‘80s and ‘90s - Ian McEwan (Salman Rushdie and Julian Barnes of The Sense of an Ending fame make up the other members of this much talked about quartet).

McEwan is one of my favourite authors. Like Amis, he is a British author with incredible talent. His books are always thought-provoking covering a multitude of themes. He has the ability to turn one event or law or day into a story of vivid characters and intriguing plot. Saturday, told all in one day, is the traumatic story of Dr Perwone's home being broken into and family being subjected to the whims of the intruders; while this is happening McEwan explores the meaning of life through Perwone's thoughts. On Chesil Beach is another masterpiece of a novel - a whole relationship laid out, analysed and dismantled - nothing really happens but really, everything happens.

Some of his books are less conceptual with a more traditional (yet still unconventional) plot such as The Cement Garden, the story of children who hide their mother's death from the authorities to avoid being taken into care and A Child In Time, the heart-breaking tale of a man who loses his daughter in a supermarket. There’s also The Children Act about a judge who has to decide whether a child can have a blood transfusion against the wishes of his parents - a novel filled with complex relationships, which is McEwan’s forte. Machines Like Me explores human relationships further by throwing a robot into the mix and seeing what happens when machine consciousness crosses human morality. Sublime.

McEwan's books are not all so heavy, however. Sweet Tooth is lighter but just as clever, following an MI5 agent who gets involved with her mark in 1970s Britain and The Daydreamer which is a series of short stories about a child who daydreams into fantastical situations.

And so back to Amis. I shall endeavour to complete a whole book of his, London Fields sits on my book shelf unopened, perhaps I will start with that? And I shall leave you with his words, which my above goal already prove: ‘As you get older you realise that all these things - prizes, reviews, advances, readers - it’s all showbiz, and the real action starts with your obituary. Writers don’t realise how good they are because they are dead when the action begins: with the obituaries. And then the truth is revealed 50 years later by how many of your books are read.’ (thanks to a great obit from the Sunday Times). Has Amis’ time only just begun?